During the early days of U.S. military involvement in World War II, the country had been caught off guard, suffering a string of devastating defeats, and left with few victories on the horizon. Most far-flung U.S. military outposts in the Pacific had been lost in mere weeks, with forces in the Philippines surrendering in April 1942, just over five months after the Imperial Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Brig. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, promoted two ranks following the successful raid, thanks B-25 aircraft plant workers in Inglewood, California, in June 1942 for their support. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Brig. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, promoted two ranks following the successful raid, thanks B-25 aircraft plant workers in Inglewood, California, in June 1942 for their support. (U.S. Air Force photo)

This string of events left much of Asia, and even Australia, open to possible invasion. With Germany virtually in control of Europe and much of North Africa, the Axis powers appeared to be holding every advantage. At the time, Americans longed for good news that would bring hope for their future.

America’s enemies at that time viewed the United States as ill-prepared to defend itself. Americans were viewed as isolationists, too weak to stand up for themselves and their allies.

That’s when a plan was devised that seemed so bold and crazy it might be impossible. Its participants are now known as the Doolittle Raiders.

A group of 80 U.S. Army Air Corps B-25 Mitchell bomber crew members, led by Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle, would launch an extremely long-range attack off the deck of an aircraft carrier against military and industrial facilities in the Japanese capital of Tokyo. The mission was so far from any Allied airfields that the 16 B-25 would then have to fly directly to China to achieve any hope of finding a safe landing.

The Doolittle Raiders knew they might not make it back. If their mission were successful, however, it would have far-reaching effects on American morale and prove that mainland Japan was not impervious to attack.

Crews and their B-25 Mitchell bombers are lined up on the deck of the USS Hornet in preparation for their raid on Imperial Japanese military and industrial targets in April 1942. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Crews and their B-25 Mitchell bombers are lined up on the deck of the USS Hornet in preparation for their raid on Imperial Japanese military and industrial targets in April 1942. (U.S. Air Force photo)

From the start, a mission like this required an understanding that it carried significant risks and a high potential for failure. A group of aircraft engineers in Minneapolis had to devise innovative ways for the B-25s to carry more than 1,000 gallons of fuel while reducing their total weight to allow them to fly extreme distances. Additionally, the medium-size bombers were never designed to take off from an aircraft carrier, which left very little margin for error.

Modifications of the B-25s started in February 1942 in Minneapolis, with training taking place the next month at a small airfield relatively hidden from the outside world at Eglin Field near Fort Walton Beach, Florida. After a little more than three weeks, Doolittle concluded that the aircrews were ready.

On April 1, 1942, the aircraft were loaded onto the aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-8), and the ship set sail from San Francisco. There was a good chance they would be spotted by Japanese patrol boats as the ship approached the heavily guarded Japanese islands. The hope was that the vast Pacific Ocean would provide the cover they needed to get the Hornet, escorted by the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and a small group of naval ships, close enough to the main island of Honshu to launch the attack without detection.

On April 18, roughly 200 miles out from the planned takeoff point for the B-25s, a small Japanese patrol boat found the task force but was destroyed by one of the escort ships. However, there were concerns that a radio message might have been sent to other ships, and the decision was made to launch the B-25s early.

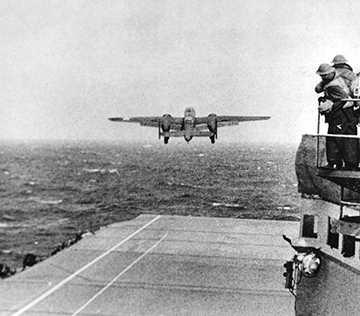

A B-25 Mitchell bomber takes off from the deck of the USS Hornet. The air crews on all 16 of the B-25 successfully accomplished the takeoff, with 15 of the aircraft successfully reaching their targets. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Lt. Col. Doolittle’s plane was the first to take off from the Hornet, with others quickly trailing in single file from the deck. The air crews joined in separate formations as they made their way to their designated targets. Everyone knew that taking off 200 miles short of their planned takeoff point reduced their chances of safely making it to airfields in China. The success of their mission, however, was now more important than their lives.

As the Doolittle Raiders approached their targets, they began to encounter heavy ground artillery fire, with few threats from the air. Their gamble of attacking the Japanese homeland caught the imperial military by surprise, with all but one American aircraft able to attack its targets.

The raid was not meant to deal a devastating blow, but it did provide a huge morale boost to the American public. The success of the mission helped pave the way for future victories.

Throughout the years, the Doolittle Raiders have come to symbolize courage and a “can do” attitude when presented with a seemingly impossible task. The people who helped prepare the B-25s, train the air crews and fly the mission created a legacy of delivering success, even in the face of impossible odds.

It’s only fitting that this legacy be imparted to the next generation of air crews and those who support them, as they fly the B-21 Raider to carry out future missions to protect our nation.

To view the Raider poster, click here.