Report by Alan Dressler

FEATURE STORY

Cosmic Game Changer: Northrop Grumman and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope

By David Larter

The report doesn’t read like something you’d expect from an acclaimed astronomer.

“Hubble Space Telescope and Beyond: Exploration and the Search for Origins” largely eschews scientific jargon and instead speaks about searching for alien life and discovering the origins of our universe.

Colloquially known as “the Dressler report” for its lead author, Alan Dressler, the 1996 document is a work of equal parts scientific inquiry and romanticism, discoursing on the cosmic mysteries to be unlocked by the successor to that National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s revolutionary Hubble Space Telescope.

The report marked a moment for the next-generation space telescope: A dividing line between a time when the Next Generation Space Telescope (NGST), as Webb was called at the time, was a collection of ideas developed inside the astronomy community for a decade or more, and the birth of a program that NASA would see through to its conclusion.

“For us, the fundamental questions were: Where did we come from and are we alone?" Dressler said, between sips of coffee at a sidewalk café in Pasadena.

“The Universe doesn't know itself except through us and creatures like us. So, the questions were 'Are there other places like this' and ‘are there other creatures like us?’ Maybe they aren't exactly like us but, of course, we were raised to expect life to look like this, so we better look for that first. And then the other question was, with our limited understanding of the origins of galaxies, ‘where did we come from?’"

Achieving the Unprecedented

The story of the James Webb Space Telescope is a 35-year journey, starting with concepts explored and developed at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) headed by Nobel Prize-winning astronomer Riccardo Giacconi, and leading through many twists and turns to Christmas Day, 2021, on the European Space Agency launch pad in Kourou, French Guiana.

It’s a story of how NASA, together with an industry team led by Northrop Grumman, achieved the unprecedented: a tool of unparalleled power and sophistication for mankind’s exploration of the deepest mysteries of our existence.

Dressler’s committee and its work product armed NASA with three things: the expressed desires of the astronomy community, a narrowed focus on an infrared observatory, and clear language to communicate it all to the public.

Alan Dressler

"Someday we will be able to describe and understand in detail the cosmic events that led to the conditions suitable for our own existence,” Dressler wrote.

“Two crucial chapters are missing from our story. Toward their completion, the Hubble Space Telescope & Beyond Committee identifies two major goals, whose accomplishment will justify a commitment well into the next century: (1) the detailed study of the birth and evolution of normal galaxies such as the Milky Way, and (2) the detection of Earth-like planets around other stars and the search for evidence of life on them.”

A Space Telescope is, in a sense, a Time Machine

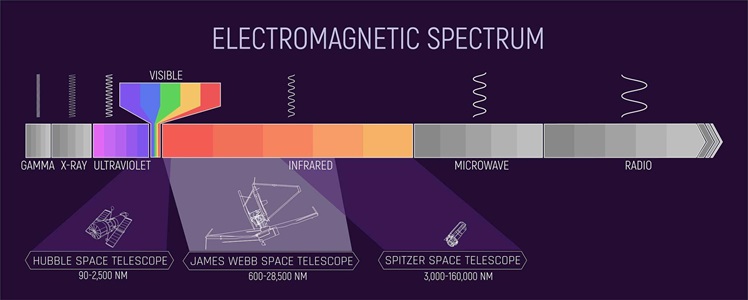

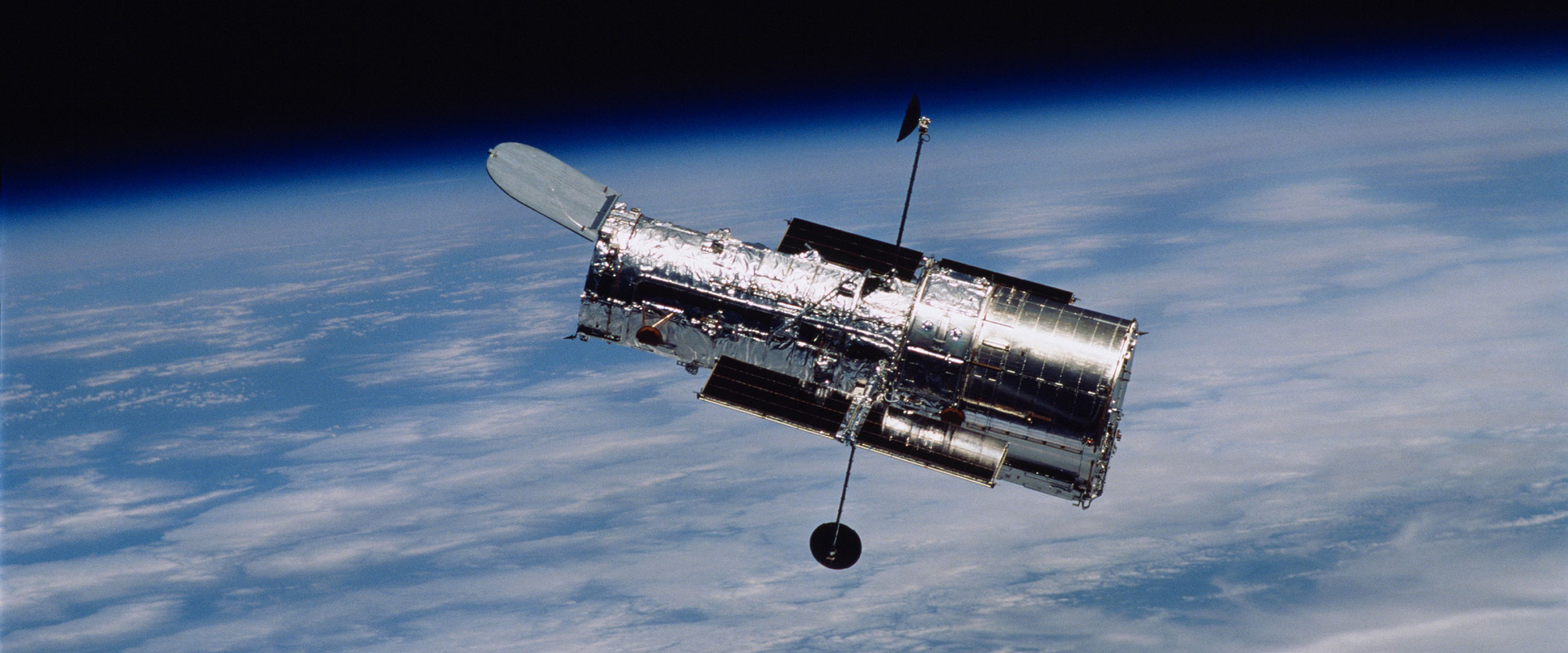

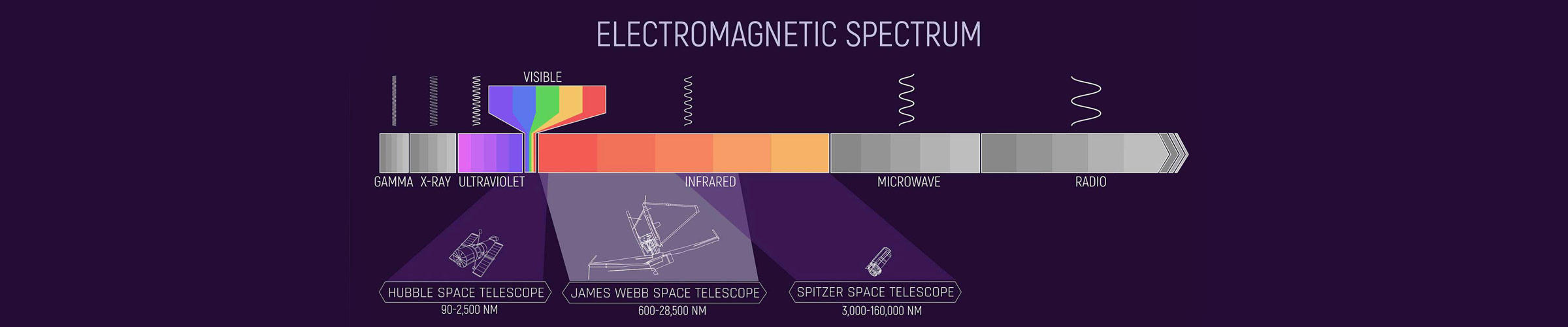

The Hubble Space Telescope can show us what the universe looked like billions of years before our ancestors crawled out of the ocean and on to dry land. But to seek out our cosmic origins from light emitted at the very dawn of the universe, astronomers need an observatory dedicated to operating in the infrared spectrum where that light can be detected.

Furthermore, using spectrographic instruments to split incoming light into its constituent wavelengths, scientists can explore the atmospheres and characteristics of distant alien planets, a crucial component of finding planets that support extraterrestrial life like ours.

To that end Dressler’s report recommended a 4-meter infrared telescope with advanced spectroscopy equipment to both see the development of the universe’s early galaxies and look for signs of habitable planets outside of our solar system.

In part one of our three-part series, we’ll explore how and why those ideas evolved into a much larger infrared observatory, why it was such an immense engineering challenge, and how Northrop Grumman engineers partnered with NASA from the program’s earliest days to realize the dreams of the astronomy community.

We’ll meet people who made the critical early decisions and contributions that eventually took the James Webb Space Telescope from a quixotic idea about the search for our cosmic origins to a $10 billion scientific instrument perched a million miles from earth that is, even now, preparing to change our understanding of the universe forever.

Go Big or Go Home

Early one morning in 1986, Deputy Director of the Space Telescope Science Institute Garth Illingworth headed into the office of STScI’s famous director, Riccardo Giacconi, who had an unwelcome assignment waiting.

“He called me in, and he told me ‘I need you to start working on the follow-on to Hubble and you need to start now because it’s going to take a long time,’” Illingworth recalled. “And at the time I remember thinking ‘Oh, my word, we’re up to our eyeballs with getting ready for launching Hubble – work to do and problems to fix.’”

Teaming Up

Illingworth took the assignment in stride, figuring that Giacconi knew what he was talking about, and got to work on what could be the next great observatory.

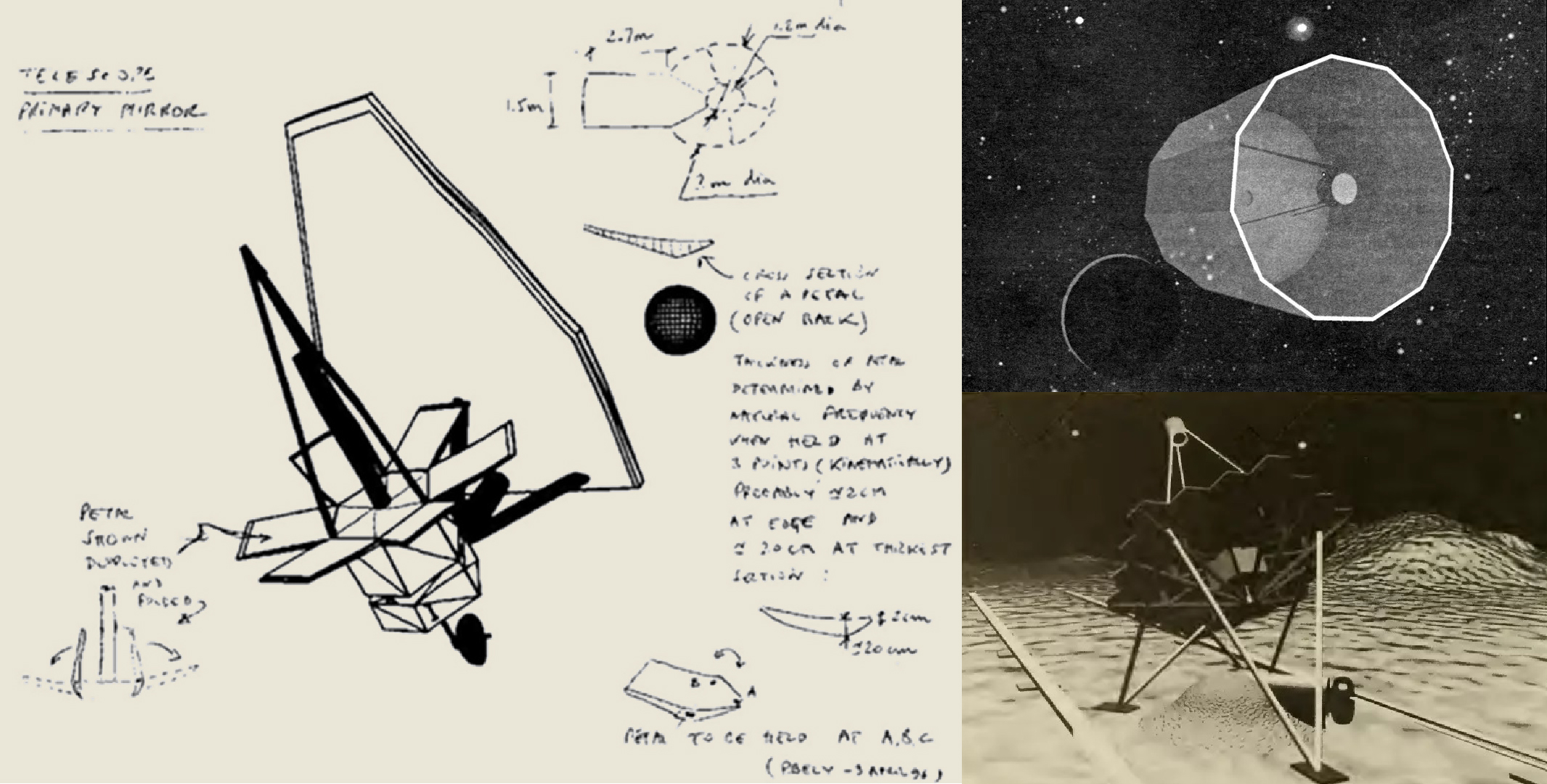

He teamed up with a European engineer Pierre Bely, who while working with STScI had already been investigating the idea of passive cooling using a sunshield that radiated heat from the sun out to space as part of a large-diameter space telescope.

In September 1989, Bely and Illingworth convened a workshop of scientists and engineers – including two from TRW’s Space Park campus in Redondo Beach – that recommended NASA explore a large-diameter (8-16 meters), passively cooled observatory either as a free-flying satellite or based on the moon, a politically popular option at the time quickly found to be impractical.

Garth Illingworth photo courtesy of TEDxPerth

The group recommended an observatory – a direct replacement for Hubble – that would operate primarily in the infrared but also allow for optical and some ultraviolet functionality. Operating a cold telescope in the ultraviolet spectrum, however, presented a mountain of technical issues, Illingworth said, and within a year he and Bely had narrowed the scope to the infrared.

Illingworth and his team continued to advance ideas through workshops, conferences, and papers. Then in 1993, at the behest of the Space Telescope Institute Council, Dressler convened his working group of astronomers to produced concrete recommendations.

Based on expected funding constraints of about $1 billion, Dressler’s report recommended a 4-meter infrared telescope that could work with a single mirror and fit inside the nose cone of a rocket.

But Dan Goldin, the NASA Administrator between 1992 and 2001, was unimpressed with the scale of what Dressler’s committee proposed and made it known in a very public way.

Goldin spent 25 years in various roles at Northrop Grumman legacy company TRW, working out of the Space Park campus in Redondo Beach.

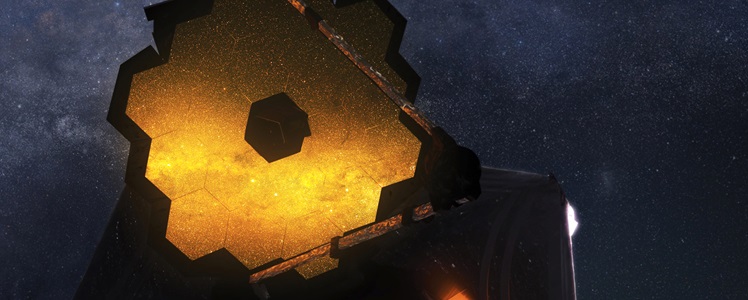

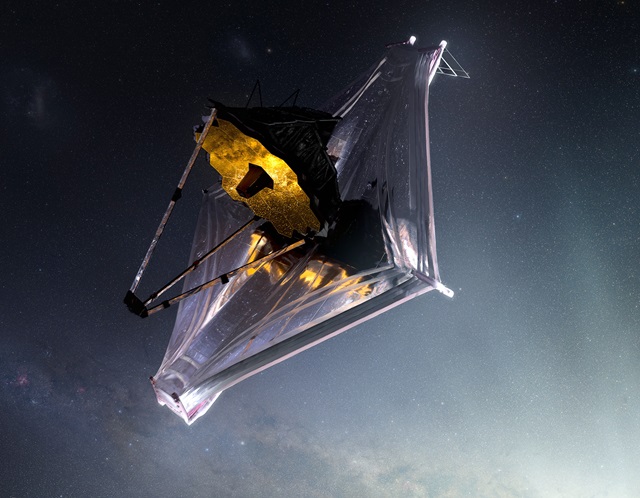

Based on his previous work, he knew constructing a deployable telescope – one that could be folded and stuffed inside a rocket faring to unfold in space – would let the agency break out of the constraints imposed by the launch vehicle and allow for a much larger, more powerful observatory.

At a 1996 meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Goldin made it known what he thought of the idea of a 4-meter mirror:

“I see Alan Dressler here,” he said, looking directly at Dressler in the front row. “All he wants is a four-meter optic… And I said to him, ‘Why do you ask for such a modest thing? Why not go after six or seven meters?’”

The call for a larger telescope received a standing ovation. Goldin’s review of the Dressler’s four-meter mirror was in: Go bigger.

In a telephone interview, Goldin said he was averse to a 4-meter optic because he didn’t believe it was big enough to accomplish the mission.

“If I’m trying to look back to the beginning of creation,” Goldin recalled. “The observatory had to be extremely cold – something on the order 25-35 degrees Kelvin – so that you don’t swamp out the signal with noise from your telescope, and that it would need to be at least six-to-seven meters in diameter. Four meters doesn’t cut it.

“So, I hear that they want to build a four-meter telescope: Okay, why do you want to build a four-meter telescope? ‘Because that's the biggest we can fit inside existing shrouds.’ Well, to heck with that. … If you want to see back to the beginning of creation, you want to see protoplanetary disks, you want to see other solar systems, you need something like 25 to 30 degrees Kelvin, and you need six to seven meters in diameter.”

Key Early Decisions

NASA selected Bernie Seery to lead the project for Goddard Space Flight Center. Seery, like Goldin, was a former Space Park physicist turned senior executive with NASA.

Goldin decided that NASA should work towards at least 8-meter deployable telescope, urging the team to stay away from smaller telescopes that didn’t sufficiently advance from what NASA had already accomplished with Hubble – calling smaller diameter telescopes “Hubble-huggers.”

Seery organized to make it happen, hammering out a working group, raising support for it with international partners and engaging industry to figure out how to give Goldin what he wanted.

But the task at hand was formidable. It was quickly clear that the engineering challenges were considerable and at a scale never previously attempted.

Actively Cool vs. Passively Cool

One of the problems that vexed Seery was how to cool the observatory enough to fulfill the science objectives.

Infrared telescopes are susceptible to interference from heat sources, like the sun and earth. The earliest studies concluded the observatory would need to maintain temperatures of about 100 degrees kelvin or -279 degrees Fahrenheit, but as the design advanced it was clear it would need to be drop even further.

That meant not only would the telescope be significantly larger than Hubble's 2.4-meter aperture, NASA needed to find a way to make it cold. Very cold.

"How are you going to get huge structure with all the bells and whistles on it to operate at cryogenic temperatures?" Seery said. "Basically, we had two choices: you could actively cool it or passively cool it."

"Active cooling" means using mechanical systems to cool the telescope and create the right operating temperatures. But for something on the scale of Webb that method presented too many technical challenges. After a quick study, the team decided passive cooling was the practical option.

Through his work at Space Park, Seery, like Goldin, knew that engineers there had experience with large, deployable gossamer structures. Both Seery and Goldin also knew of a classified independent research and development project out of Space Park that used a deployable 8-meter, radio frequency telescope that could open possibilities for the NGST, Seery recalled. Previous instruments produced by Goddard – the Cosmic Background Explorer satellite – also explored the concept, employing a much smaller multi-layer sun shield for passive cooling.

Using a deployable sunshield constructed of multiple, gossamer layers of reflective insulating material that radiates its heat into space allows the ambient temperature of space (about 2.4 kelvin) to accomplish most of the necessary cooling.

"We decided very early on with a quick trade study to go for a deployable sunshield," Seery recalled. "And we actually felt confident because it turns out that TRW specialized in the deployment of large gossamer-like structures for their various RF antennas. It’s something that had been done before.”

Dan Goldin (left) and Bernie Seery

Once NASA accepted the idea of a passively cooled telescope, few people could have predicted the sun shield would end up being one of the trickiest components the entire design. Another big issue, instead, was occupying Seery’s mind: the primary mirror.

Choosing the right materials for the mirror segments was critical.

It was clear from the start that to create a large-diameter, deployable telescope, the mirror would need to be composed of interlocking mirror segments instead of one large mirror, which is what is Hubble operates.

Materials like metals and glass expand and contract based on temperature, so for a large-aperture, segmented telescope, selecting a material that performed in predictable ways over a range of temperatures was critical. If there are major temperature differences in various places on the primary mirror, the optics could be distorted or misaligned, spelling disaster for the mission.

"We had multiple material systems that we could choose from," Seery recalled. "We had glass that was ultra-lightweight – well beyond what was available during Hubble's development. And then we had beryllium."

NASA and industry divided into various camps, with some supporting glass mirrors and varying numbers of actuators used to align and adjust them based on thermal conditions, and others supporting beryllium, which offered its own advantages, Seery recalled.

Some argued that glass is easier to work with, has good thermal properties and doesn’t corrode. Team Beryllium saw that the thermal and expansion properties of their selected metallic material were more stable over a range of operating temperatures than glass. If they went with glass, engineers would need to compensate for those variances elsewhere in the design, which would be extremely difficult to execute.

And the Winner Is…

Throughout the process, the team at Space Park was involved at every step, recalled Charlie Atkinson (pictured), Northrop Grumman’s chief engineer for the James Webb Space Telescope.

Atkinson came to Space Park in 1998 to work on what was then known as the next-generation space telescope after working at Kodak on the Chandra X-Ray Telescope, another Space Park product.

From the earliest days, Northrop Grumman’s engineers waded in with both feet to help hammer out a path forward, Atkinson said.

“We were very involved in the early concept development,” said Atkinson. “We had a whole team of people working on it, but it was early days.

“We hadn’t yet decided on what orbit it should go to, what the aperture configuration was going to be – we knew we wanted it to be of order 10 meters, but nothing more than that.

“What’s the shape of the aperture going to be and how you gonna get it into space? What is the spacecraft bus gonna look like? What’s the sunshield going to look like? (Goddard was actually looking at an inflatable sunshield at one point.) What are the mirrors going to look like and what are they going to be made of?”

Revolutionary – Not Evolutionary

At NASA, Seery’s Goddard team convened a working group with the Marshall Space Flight Center, STScI and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory on a “yardstick” concept that would keep the industry teams “thinking ‘next generation’ and revolutionary – and not an evolutionary design,” Seery recalled.

With the “yardstick” in mind, the team at Space Park hashed out a working concept and prepared to compete for the upcoming prime contractor job on Webb. As the process moved forward, the Space Park team made a strategic decision that shaped the outcome of the competition: instead of competing against Ball Aerospace for the Webb contract, they’d join forces, Atkinson said.

“We looked at it and realized that where our capabilities were strong – systems engineering and deployables – and their capabilities were strong – optics – it just meshed really nicely.

“So, we made that agreement and went into the proposal with both of us working together and the team really meshed well as a result.”

The issue of glass versus beryllium was one that the Space Park team and Ball settled early, said Josh Levi, a Northrop Grumman engineer who has been on Webb almost from the beginning.

“We – Northrop Grumman and Ball – recognized the material property benefits that Beryllium had to offer and the manufacturing benefits that glass had to offer,” he said. “It did not help, though, that the ultra-low expansion (ULE) glass mirror cracked during cryogenic testing. So, the thermal conductivity, thermal performance, low thermal expansion at cryogenic temperatures – from a material property perspective, everything's just a little bit better with beryllium.

We even investigated making the entire telescope structure out of beryllium, but that would have been prohibitive for a number of reasons: it’s just harder to work with.”

By 2001, the Space Park team submitted its proposal to NASA in a bid to be the prime contractor for the next-generation space telescope, confident in the choice of beryllium as the right material for the primary mirror, but ready to go with glass if that’s what NASA selected, according to Atkinson.

On September 10, 2002, after years of dreaming, note-book sketches, committees, conceptualizing, NASA announced that the Space Park team would be prime contractor for the next-generation space telescope, newly christened the James Webb Space Telescope.

Editor’s Note: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is, as former Northrop Grumman Webb Chief Engineer Jon Arenberg describes it, “an archetypal act of collective genius.” No single article could possibly capture all the profound contributions from so many who realized the Webb vision. Many pivotal figures in Webb’s four-decade journey, including Webb’s senior astrophysicist John Mather, STScI astronomer Peter Stockman, and NASA’s longtime headquarters program scientist Eric Smith, are not covered in this series. We thank everyone who took time to speak with us to help us share Webb’s amazing story.

Why Bigger is Better

The history of astronomy – from the first tiny glass lens telescopes in the 1600s to the 200-inch giant mirror telescope at Mt. Palomar – is a steady march toward finding ways to increase the size of telescopes, and hence the amount of light that can be collected and, critically important, higher resolution to show more detail.

Just like a larger pair of binoculars or a larger camera lens lets us see distant objects better, the larger the “aperture” of a telescope – or the diameter of the primary mirror – the better you can see astronomical objects that are very far away and really faint.

Astronomers on the ground have steadily pushed the boundaries of telescope size. The ground-based Keck Telescope in Hawaii was the first to use hexagonal mirror segments to expand the size of the primary mirror to 10 meters. Webb used the same approach for its 6.5-meter aperture primary mirror, the largest in space. The segmented mirror technology enabled a huge leap from 8-10 m telescopes of today to the 30 to 40-meter telescopes of tomorrow.

Image: NASA GSFC/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez

Why Infrared?

Because the universe is expanding, the earliest light is being stretched to longer wavelengths as distant objects move away from us. Scientists often described this phenomenon using the analogy of a train's whistle that has a higher pitch as it comes towards us but lower pitch as it moves away: The doppler effect.

On the electromagnetic spectrum, objects moving away from us emit light that is redder because the wavelengths are stretched due to the speed it moves away. Conversely, any objects coming towards us would look bluer and have shorter wavelengths since their light is being compressed. Scientists describe that light from retreating objects as being “redshifted,” a phenomenon first discovered by Edwin Hubble, namesake of the Hubble Telescope.

Once light wavelengths lengthen enough, you’ll need an infrared telescope to see it. Hubble is so powerful it could see redshifted galaxies, but it wasn't strong enough to see the reddest light from the earliest galaxies. To see that light, you need to operate in the infrared spectrum.

Ergo: Astronomers knew, even before Hubble launched, that they’d need a very large aperture, infrared telescope to see light from near the beginning of time.

Image: NASA and J. Olmsted (STScI)