Northrop Grumman has a rich history of defining possible.

A Riveting History

By Caroline Mroz

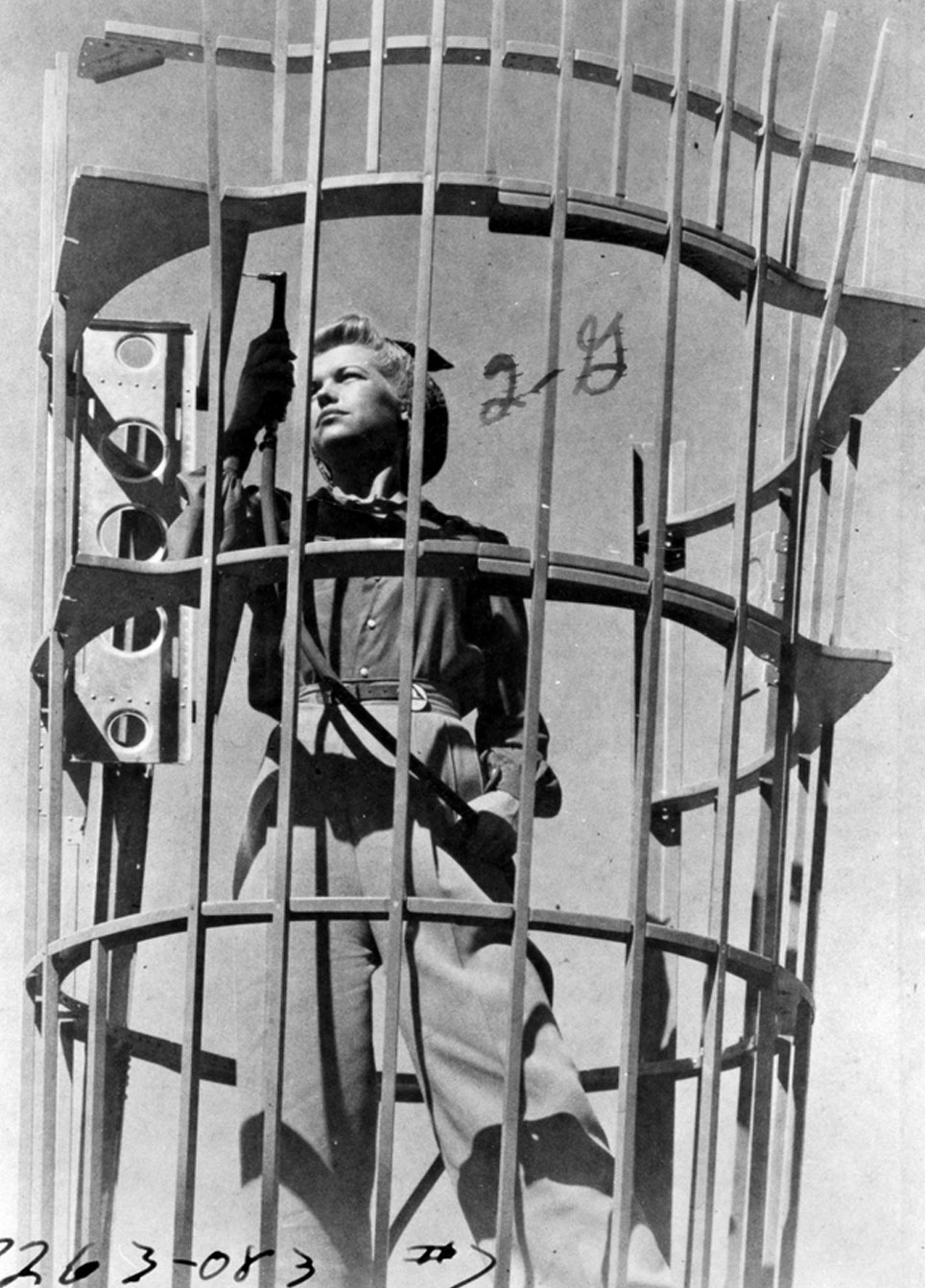

On a blustery Friday in November 1943, reporters lined the Grumman runway in Bethpage, New York, jostling for a glimpse of Barbara Jayne, Elizabeth Hooker and Teddy Kenyon. The women were test pilots, estimated by “Grumman Plane News,” the company newsletter, to be “the only women pilots in the country who test airplanes for a living.”

The pilots posed for photos in their flight suits, answering questions about how they learned to fly and their ability to execute flight techniques. Then, they boarded their planes — Barbara and Elizabeth flew Hellcats, while Teddy tested an Avenger — and demonstrated a test flight, each executing a perfect landing.

A few years earlier, this profession would have been unthinkable for a woman. Women also weren’t inspectors, plane captains, assemblers, engineering aides, production planners or riveters. However, as American men were drafted into service for World War II, millions of women stepped into these roles at production facilities across the country, including at Northrop Grumman heritage companies, where women comprised 35% of the World War II workforce.

Fueling the War Effort

The United States entered World War II in December 1941 and, the following year, Grumman War Production Corps hired its first female employee. By April 1943, Grumman’s female employees counted in the thousands, and the company was recruiting 5,000 additional women to meet increased production demand. To support their new female workforce, the company established nursery schools for the employees’ children, organized women’s sports leagues and offered on-site counseling to help female employees transition into their new roles.

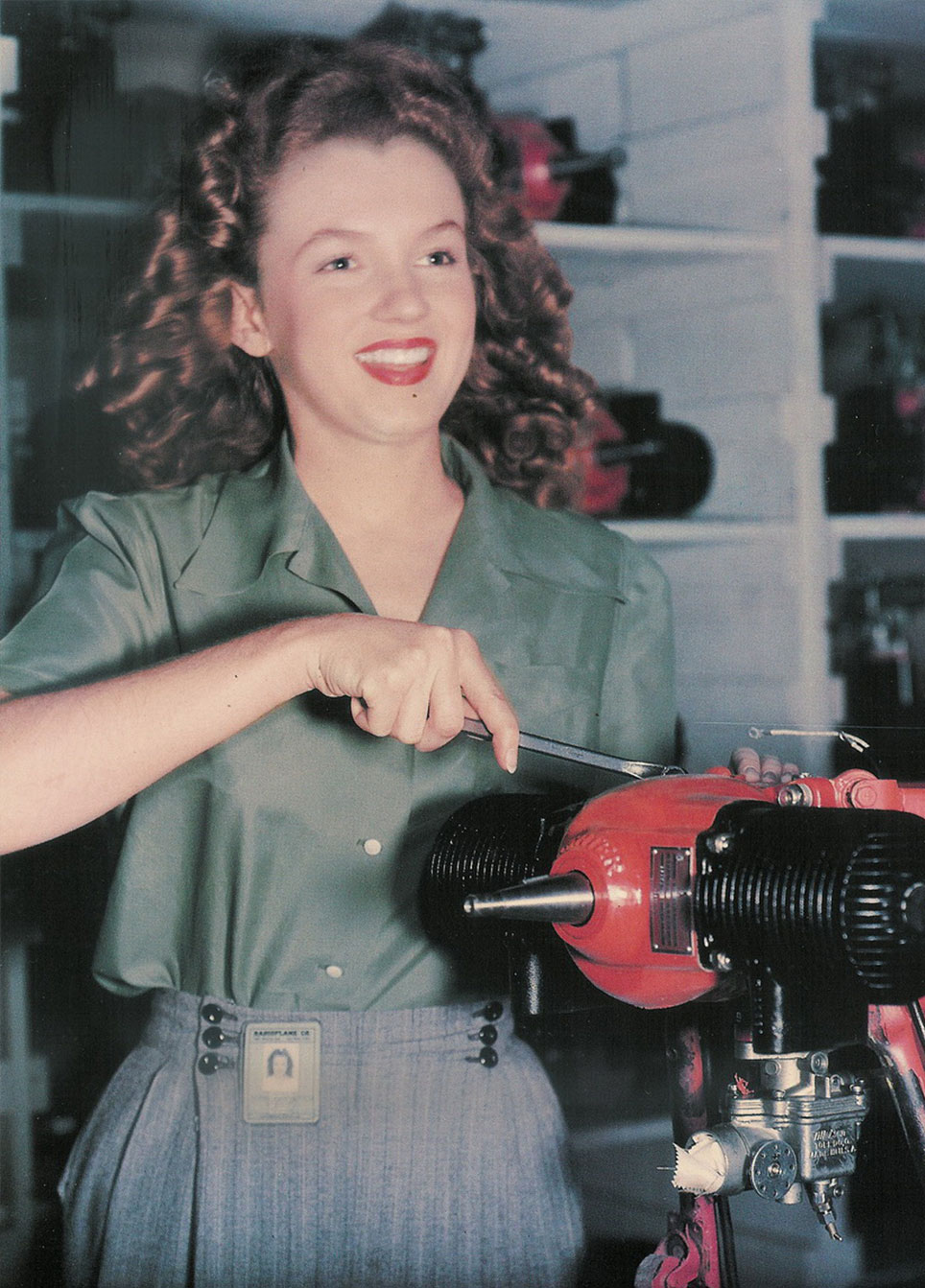

Across the country, in Burbank, California, Radioplane — a target drone manufacturer that was acquired by Northrop in 1952 — also employed many women, including Norma Jean Dougherty. Norma, the wife of a merchant marine, inspected and sprayed parachutes with fire retardant; a photograph of her at work helped launch her Hollywood career as Marilyn Monroe.

Like Norma Jean, many of the women had personal connections to the war — fathers, partners or loved ones who were serving or had died in combat — and took these roles to play their part in the war effort.

“I felt that my husband was doing his share and there was no reason for me to stay at home,” bench worker and military spouse Claire Van Derlofske told “Grumman Plane News” in April 1943. “I like my job very much because I feel that I am really helping my husband.”

These roles were also an opportunity to learn new skills. Many of the new female employees had no prior technical experience, but accounts from the time praise their ability to tackle new challenges with enthusiasm. As just one example, a team of Grumman female employees won a riveting contest at a War Exposition in Nassau, New York, driving 187 perfect rivets in just 10 minutes. Notably, Martha Mystowski, who operated the riveting gun, had never worked with that type of rivet prior to the competition.

“I was scared but decided to take a deep breath and forget that people were watching me,” Martha told “Grumman Plane News.” “You just can’t drive rivets with a shaky hand.”

An Enduring Legacy

The can-do spirit of these patriotic women was captured in the now-iconic illustration of Rosie the Riveter, first featured on a poster produced by Northrop Grumman heritage company Westinghouse Electric. Rosie wears a shop uniform and kerchief — both of which were issued to each riveter upon hire — and flexes her bicep. In response to this poster, as well as Norman Rockwell’s imagining of Rosie for a May 1943 cover of “The Saturday Evening Post,” women working in war production began referring to themselves as “Rosies.”

Rosies came from all walks of life, from Grumman’s first plane captain, 19-year-old May Nostrand, to bench worker Rose Robbins, a mother of three servicemembers who volunteered at the Army Hospital in addition to her work at Grumman. The magic of Rosie the Riveter was that she resonated with women working across diverse roles and locations during World War II, and her impact has continued to echo across generations.

Northrop Grumman Project Manager Heather Ann San Nicolas said she’s felt a connection to the Rosies since she was a little girl. Reflecting on her career path, which has taken her from the U.S. Air Force to Northrop Grumman, where she is now pursuing a master’s degree in systems engineering, Heather Ann said she’s honored their legacy.

“Through it all, I've strived to empower fellow women, proving that resilience and determination know no bounds,” said Heather Ann. “My story is a testament to the enduring spirit of women like Rosie, who dared to defy expectations and forge their own path.”

The can-do spirit of these patriotic women was captured in the now-iconic illustration of Rosie the Riveter.

Grumman Rosie Lee Allessio wears her work uniform, which she calls a "zoot suit Grumman special." (Photo courtesy Lee Allessio Collection)

Read more about Life at Northrop Grumman and learn more about our company’s heritage.

Life at Northrop Grumman

Your work at Northrop Grumman makes a difference. Whether you want to design next-generation aircraft, harness digital technologies or build spacecraft that will return humanity to the moon, you’ll contribute to technology that’s transforming the world. Check out our career opportunities to see how you can help define possible.